Graft versus Host Disease (GvHD)

Graft versus host disease (GvHD) is a complication that can arise following a bone marrow or stem cell transplant.

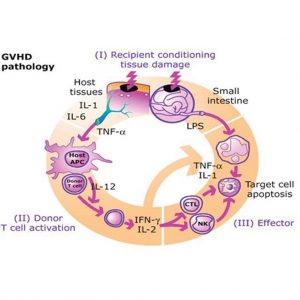

GvHD occurs when particular types of white blood cell (T-cells) in the donated bone marrow or stem cells attack your own body cells. This happens because the donated cells (the graft) see your body cells (the host) as foreign and attack them.

It is difficult to predict who will develop GvHD after a transplant. We don’t know exactly, but somewhere between one and four out of every ten people who have a donor transplant will develop some degree of GvHD. Some people have a very mild form that doesn’t last long. For others, GvHD can be severe, even life threatening in a few cases. Some people may have GvHD over many months, or even years.

How GvHD develops

GvHD happens because the transplant affects your immune system. The donor’s bone marrow or stem cells will contain some T-cells: a type of white blood cell that helps us fight infections. T-cells attack and destroy cells they see as foreign and potentially harmful, such as bacteria and viruses. Normally T-cells don’t attack our own body cells, because they recognise proteins on the cells called HLA (human leukocyte antigens). We inherit our HLA from our parents. Apart from identical twins, HLA is unique to each person.

Before a bone marrow or stem cell transplant, you and your donor have blood tests to check how closely your HLA matches. This test is called tissue typing. If you and your donor have very similar HLA, the chances of you developing GvHD are reduced. The more differences there are between your HLA and your donor’s, the more likely you are to get GvHD.

After a transplant your bone marrow starts making new blood cells from the donor stem cells. As new T-cells develop, they recognise the new environment and are tolerant of it. Until that point, T-cells donated in the bone marrow sample have the donor’s HLA pattern. They may recognise the HLA pattern on your body cells as different (foreign) and may begin to attack some of them.

GvHD can affect different areas of your body. Most commonly affected are the skin, the digestive system (including the bowel and stomach) and the liver.

Types of GvHD

GvHD is categorised according to how soon it starts after a transplant. Doctors also look at what parts of the body are affected and how severely. The types of GvHD are:

- Acute GvHD

- Chronic GvHD

- Late acute GvHD

- A combination of late acute GvHD and chronic GvHD.

Acute GvHD

Acute GvHD generally occurs within 100 days of your transplant, but it can sometimes happen later. Acute GvHD can be mild or severe. It starts after the new bone marrow begins to make blood cells. Doctors call this engraftment, and it usually happens about 2–3 weeks after your transplant.

This type of GvHD often starts with a rash on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, on the ears or on the face. The rash may be itchy or painful. Acute GvHD can also affect the mouth, gut (digestive system) and liver, with the potential to cause diarrhoea, sickness, loss of appetite and yellowing of the skin (jaundice).

Chronic GvHD

Chronic GvHD starts more than 100 days after your transplant. You are more likely to get it if there has been acute GvHD, but it can happen even when someone hasn’t had acute GvHD.

Like acute GvHD, chronic GvHD may affect the skin, gut, liver or mouth. But it can also affect other parts of the body, such as your eyes, lungs, vagina and joints. Chronic GvHD may be mild or severe, and for some people it can go on for several months or even years.

A combination of late acute GvHD and chronic GvHD

Late acute GvHD is defined as starting after day 100 and an overlap syndrome with features of both acute and chronic GvHD. They are both more likely to happen after mini transplants (reduced intensity conditioning), which doctors now use more often.

Risk factors for GvHD

A number of factors can increase the risk of GvHD. These include the following:

Unrelated donor transplants

If the donor is unrelated, the risk of developing GvHD is greater than if the donor is a brother or sister (sibling).

Mismatched donors

If a mismatched transplant is used, the donor will be as close an HLA match as possible. But sometimes the best available bone marrow donor is still a slight mismatch. This increases the risk of GvHD.

High numbers of T-cells in the donated stem cells or bone marrow

Donated stem cells or bone marrow that contain high numbers of T-cells are more likely to cause GvHD. This is called a T-cell replete stem cell transplant. While this type of transplant may cause more GvHD, it may also lower the chance of rejection.

Age

The older you and your donor are, the greater your risk of developing GvHD.

Having a donor of a different sex from you

If your donor is a different sex from you, the risk of GvHD is slightly increased. This is particularly true if a male has a female donor who has had children or been pregnant in the past.

Testing positive for cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (pronounced sy-toe-meg-aloe virus) is also called CMV. It is a very common virus that is usually harmless. Over six out of ten people (60%) in the general population test positive for CMV. In other words, they have CMV antibodies in their blood. If you are CMV negative but your donor is CMV positive, then your risk of GvHD is higher.

The effects of GvHD

GvHD can be unpleasant and reduce quality of life. In severe cases it can be life threatening. There are treatments to prevent GvHD, and doctors will fine-tune the use of these treatments. The treatments try to lower the risk of serious GvHD as far as possible but still keep some benefits. This may help stop rejection of the transplant.

Treatments for GvHD

Both before and after a transplant, doctors use treatments to reduce the chance of GvHD occurring. These treatments destroy T-cells. T-cells are white blood cells that are part of the immune system. They attack cells that are foreign to the body. So, reducing the number of T-cells in the donor marrow or stem cells (the graft) reduces GvHD. But sometimes having GvHD is a good thing, so doctors try to strike a balance between preventing severe GvHD and getting some possible benefits from mild GvHD.

Treatment before your transplant

You will have a drug called cyclosporin (also called Deximune, Neoral or Sandimmun). This drug works by reducing the number of T-cells in your donated marrow or stem cells. You start having it by drip (intravenously) a couple of days before your transplant. Before you go home, you start taking it daily as a capsule. You usually keep taking cyclosporin for about six months after the transplant.

An alternative to cyclosporin, especially if it causes too many side effects for you, is a combination of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and tacrolimus.

You might have treatment with other drugs before your transplant. These could be alemtuzumab (Campath) or antithymocyte globulin (ATG). Newer drugs being tried include tacrolimus or sirolimus (Rapamide). These drugs target and destroy your existing T-cells and the new T-cells you make after your transplant. This helps prevent you rejecting the donor marrow or stem cells, and reduces your chances of developing GvHD.

Removing T-cells from the bone marrow or stem cells

Your doctors can remove T-cells from your donor’s bone marrow after it has been donated, or during the donation of stem cells. This is called T-cell depletion.

Treatment after transplant

Patients who require continuing treatment for GvHD are likely to be taking a number of drugs, including prednisolone, cyclosporin and MMF. Other treatments include extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP), which is when blood is removed from the patients, the white cells are separated and have a light shone at them, and then everything is replaced. The procedure generally takes 2–3 hours and initially happens twice a week on consecutive days. As the patient improves, it is given every two, four or six weeks.

More information

Read more about the different types of CGD.

Our website contains a wealth of information to help and support you. If you are not able to find the answer to a specific question, feel free to contact us using the form at the bottom of the page or by emailing or calling us. We are here to help.